Imagine the challenge: there is a place of astonishing natural beauty, biodiversity and cultural significance, admired by many and officially protected.

Yet, beneath its surface lies one of the world’s largest natural gas reserves.

How do you square the apparent circle and both preserve all of the unique environmental aspects of the place, while also ensuring that your citizens and future generations are provided with the energy they need?

It is a question facing many around the world currently, as governments, corporations and communities try to puzzle out the difficult practicalities of the energy transition.

In the UAE, this was not some abstract debate. Recently, a range of government agencies, oil and gas majors and environmental guardians have come together to try and solve the puzzle.

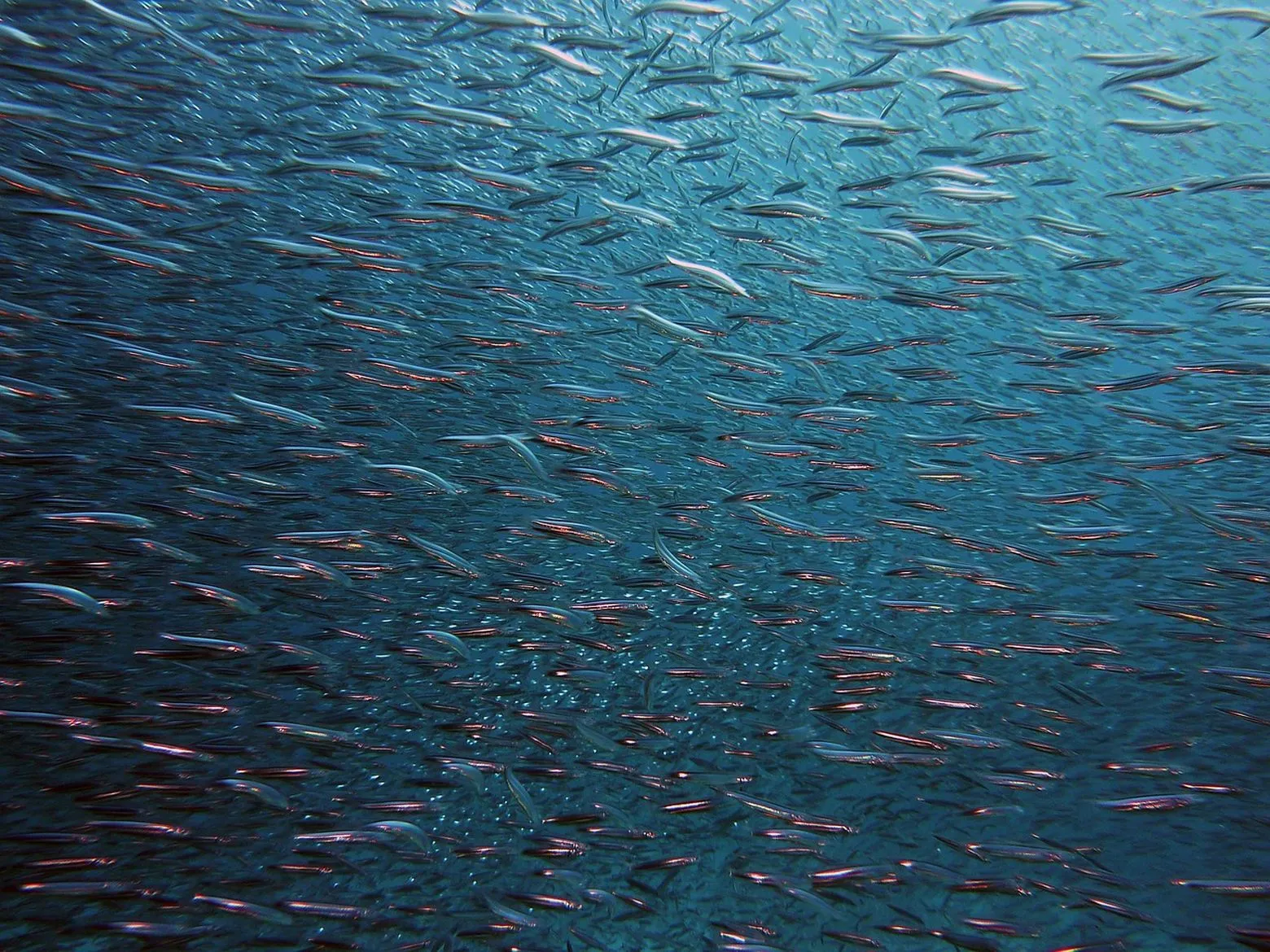

The subject was the 545,000-hectare Marawah Marine Biosphere Reserve. Now a UNESCO designated area, it was also the first marine protected area ever established in the UAE.

Some 60% of the world’s endangered dugong – or sea cow – live in the reserve, which is also a crucial nursery for many fish species. The rare hawksbill and green turtles also nest in this offshore ecosphere, while its lagoons are home to thousands of migratory birds and its coastal mangrove swamps a major carbon sink.

The area also has major cultural and historical significance. Within it is the island of Dalma, home to some of the earliest civilisations in the Gulf, with settlement dating back 7,000 years. The waters of the reserve have also long been traditional grounds for pearl diving – on which local economies depended for centuries and which has recently been undergoing a revival.

Yet, the reserve also includes the Ghasha Concession – a chain of offshore undersea fields that could produce up to 1.5 billion standard cubic feet of gas per day (bscfd) by 2030. This would be enough to meet 20% of the UAE’s entire gas needs.

With the country’s Supreme Petroleum Council (SPC) and the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) both committed to creating gas self-sufficiency for the UAE under their Smart Growth Master Plan, Ghasha therefore seemed too good an opportunity to miss.

Yet, how to extract this glittering prize without disturbing the delicate and priceless environmental balance above it?

ADNOC eventually enlisted a long list of companies and experts to come up with an answer.

Bechtel was engaged for the front-end engineering and design (FEED), the National Marine Dredging Company (NMDC) was awarded the contract for dredging, land reclamation and marine construction, KBR rendered project management services as part of the FEED work, Artelia carried out detailed engineering work and Fugro conducted geophysical and geotechnical services. Later, two engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts were awarded on the one hand to a consortium of the National Petroleum Construction Company (NPCC) and Saipem, and on the other, to Italy’s Tecnimont.The concession itself is divided up between ADNOC, Wintershall Dea, Eni and Lukoil.

Meanwhile, the Environmental Agency in Abu Dhabi (EAD) engaged Arcadis to deliver a range of environmental services, including the final Health, Safety and Environmental Impact Assessment (HSEIA).

The design of the project is extremely ambitious and advanced. It centres around a series of 11 artificial islands built along two causeways, also connected to an expanded existing island, Al Ghaf. This enables the project to extend over the different fields – Hail, Ghasha, Dalma, Nasr and Mubarraz – which are located in shallow waters of 0-15 metres depth.

Remote access technologies are also being deployed, operated from a control centre at Al Manayif, while onshore, a carbon capture and storage (CCS) facility will both remove carbon and produce hydrogen, with renewable energy and nuclear supplying the electricity for this.

NMDC’s artificial islands provide a number of advantages both for extraction and the environment.

First, wells become land based, enabling the deployment of low-cost land rigs for the drilling. These will also offer better drilling reach, in comparison to offshore rigs, using extended reach drilling (ERD) technology. With this, after initially drilling down vertically, wells can drill out horizontally, targeting reservoirs that may be considerable distances from the original well. This dramatically reduces the number of well heads required.

The islands also reduce the number of dredging wells required for the project – some 100 of these were estimated to be necessary, if the project had followed traditional offshore methods. This reduces the impact on the seafloor and local marine environments, while the artificial islands also provide additional marine and coastal habitats. The aim is to use the new shorelines and bays to repopulate the area with new fish stock. The EAD has also required zero-discharges from the project, a rescue and rehabilitation programme for endangered sea turtles and nesting platforms for ospreys – one of the region’s rarer birds.

The CCS element of the project should also see some 1.5 million tonnes per year of CO2 captured from the concession’s ultra-sour gas. This is heavy with hydrogen sulphide and CO2, with the project’s advanced decarbonisation plant turning this disadvantage into an advantage as it strips out these elements – helping the project towards net zero.

Imaginative and innovative solutions have been used to address a challenging problem, in other words – with lessons here for other energy transition projects, as they try to balance growing demand with environmental and cultural patrimony.

Powered by